Return to James S. McDonnell Prologue Room

DC-1 Request for Proposal

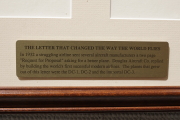

Just inside the entrance is the historic "letter that changed the way the world flies," the RFP which led to the development of the DC-3.

In the early 1930s, Boeing consisted of both an airplane manufacturing division and an airline division, the latter eventually becoming United Air Lines. Boeing's manufacturing division produced the Model 247, a new plane with exceptional capabilities, but which was initially available exclusively to United; this did not sit well with TWA.

As described in A Brief History of the Boeing Company,

The Model 247, one of the first modern passenger transports, had been built for United Air Lines, part of Boeing's multifaceted United Aircraft and Transportation Corp.

With its powerful engines and its single cantilevered wing, the 247 gave United the ability to offer 10 round trips daily between New York and Chicago. Although regularly scheduled passenger service began in 1933 with the 247, its success was also its downfall.

Competitors of United Air Line could not order the new 247 until after the first 60 airplanes had been delivered to United. However, Jack Frye, vice president operations of Transcontinental and Western Airways (now Trans World Airlines), also wanted some 247s. Boeing Aircraft president Claire Egtvedt asked United Aircraft and Transportation's board of directors to allow TWA to order 247s after the first 20 had been delivered. The board refused.

Therefore, TWA sent out a request for bids to build a three-engine transport. The Douglas Aircraft Company in Santa Monica, Calif., won with the twin-engine DC-1, which was larger and faster than the Model 247. The prototype DC-1 and its production version, the DC-2, eventually refined as the legendary DC-3, quickly attracted new customers. By 1939, an estimated 83 percent of the U.S. domestic scheduled airline service was handled by the DC-2 and the DC-3.

The 247 and the Douglas transports marked the beginning of contemporary commercial aviation and paved the way for development of large, multiengine aircraft.

dscc8853.jpg |

dscc9989.jpg |

dscc8856.jpg |

dscc8858.jpg |

dscc8864.jpg |