| Prev |

heroicrelics.org Kansas Cosmosphere Site Index RD-107 Engine Gallery |

Next |

dsca0367.jpg

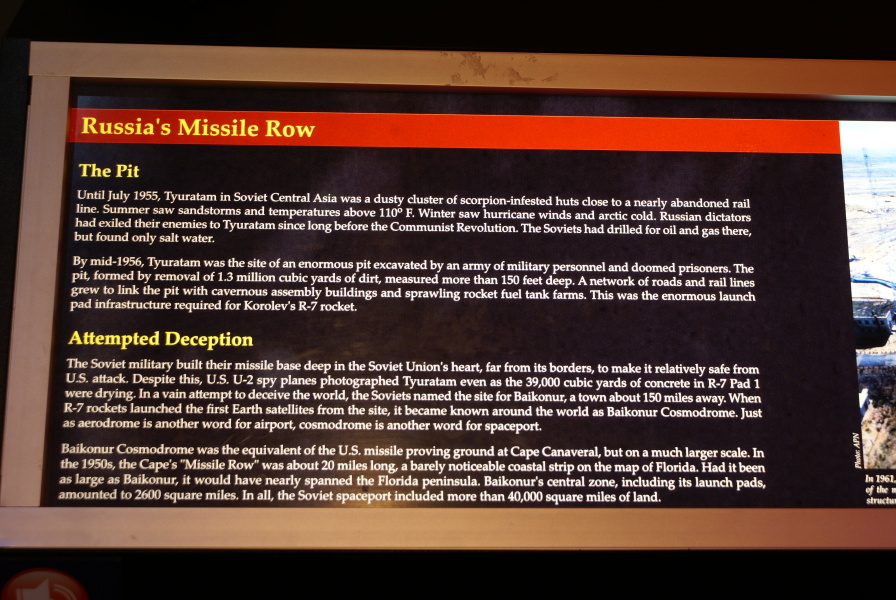

One of the signs accompanying the engine. It reads

Russia's Missile Row

The Pit

Until July 1955, Tyuratam in Soviet Central Asia was a dusty cluster of scorpion-infested huts close to a nearly abandoned rail line. Summer saw sandstorms and temperatures above 110° F. Winter saw hurricane winds and arctic cold. Russian dictators had exiled their enemies to Tyuratam since long before the Communist Revolution. The Soviets had drilled for oil and gas there, but found only salt water.

By mid-1956, Tyuratam was the site of an enormous pit excavated by an army of military personnel and doomed prisoners. The pit, formed by removal of 1.3 million cubic yards of dirt, measured more than 150 feet deep. A network of roads and rail lines grew to link the pit with cavernous assembly buildings and sprawling rocket fuel tank farms. This was the enormous launch pad infrastructure required for Korolev's R-7 rocket.

Attempted Deception

The Soviet military built their missile base deep in the Soviet Union's heart, far from its borders, to make it relatively safe from U.S. attack. Despite this, U.S. U-2 spy planes photographed Tyuratam even as the 39,000 cubic yards of concrete in R-7 Pad 1 were drying. In a vain attempt to deceive the world, the Soviets named the site for Baikonur, a town about 150 miles away. When R-7 rockets launched the first Earth satellites from the site, it became known around the world as the Baikonur Cosmodrome. Just as aerodrome is another word for airport, cosmodrome is another word for spaceport.

Baikonur Cosmodrome was the equivalent of the U.S. missile proving ground at Cape Canaveral, but on a much larger scale. In the 1950s, the Cape's "Missile Row" was about 20 miles long, a barely noticeable coastal strip on the map of Florida. Had it been as large as Baikonur, it would have nearly spanned the Florida peninsula. Baikonur's central zone, including its launch pads, amounted to 2600 square miles. In all, the Soviet spaceport included more than 40,000 square miles of land.

| Time picture taken | Sat Dec 7 11:12:28 2013 |

| Location picture taken |

Outside the Blockhouse Gallery Hall of Space Kansas Cosmosphere Hutchinson, KS |

| Prev |

heroicrelics.org Kansas Cosmosphere Site Index RD-107 Engine Gallery |

Next |