| Prev |

heroicrelics.org USSRC Saturn/Apollo Reunions Site Index Third Annual Saturn/Apollo Reunion (2006) Gallery |

Next |

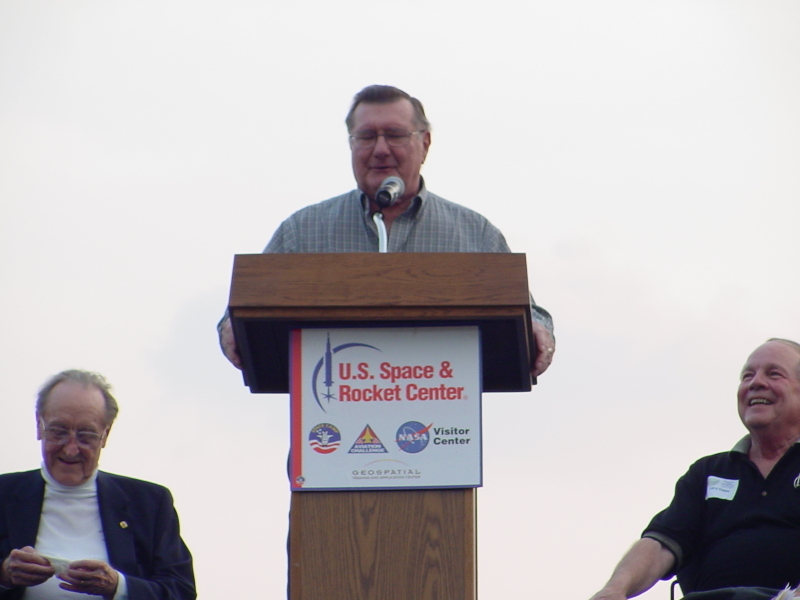

Dick Gordon

Here are astronaut Dick Gorden's remarks:

Thank you very much. Good evening, ladies and gentlemen.

I'm going before Walt to speak tonight, because I showed him my notes when he first got here and I know if he had gone first, I would have nothing to say [laughter].

What I'd like to do tonight is: I'm kind of a history buff, and I like people to go back and see where they were and what they've done, because if we don't understand it, we won't know where we're going in the future.

But think about this. Somebody said that's a Saturn I [the speakers are facing the Saturn I in the Rocket Park], and I truly believe that. Wernher von Braun and his people worked on a design of that vehicle in April of 1957. It was designed to provide 1.5 million pounds of thrust to put objects into orbit. It first flew in October of 1961. It flew 10 flights, the final being flown in July of 1965. The last four flights were somewhat interesting in this regard, in that two flights from the last, it put a boilerplate command module into orbit. The last two flights launched Pegasus into orbit around this earth.

But we weren't through there; the Saturn series continued. And we needed a vehicle that would put the command and service module into orbit, so the Saturn IB was born. Saturn IB provided four manned flights in our program. Walt had the pleasure of flying on the first one, Apollo 7, in October of 1968. The following years it provided flights to Skylab, in which three manned flights flew on that vehicle. So, it served a great purpose in that series. We used that vehicle to launch the command and service module.

The series continued, and I don't know how we went from the S-IB to the Saturn V, but we did, and George tells me that it was probably because we had five engines on it [chuckles]. But in January of 1962, the directive was given to design the Saturn V. Its function was to take people to the moon.

At that time, there were three discussions of, "How do we go there?" One series said, "Let's do it just like Jules Verne did -- just launch a vehicle like the Columbiad and go direct." Well, that's hardly feasible in terms of capability.

The next argument or discussion of how to do it was earth-orbit rendezvous, which Wernher von Braun was a very, very strong proponent of that. We would launch several vehicles, assemble them in earth orbit, and then proceed to the moon and accomplish our lunar landing.

The third concept was what we called LOR, or lunar orbit rendezvous.

This discussion, these arguments, raged for quite some time. And in 1962, also it was decided that lunar orbit rendezvous will be chosen. It provided us with more reliability. It reduced the schedule for putting a man on the moon by several months. Wernher finally came around and went along with the LOR, but I think the thing that pushed him was his people finally were convinced, and said, "This method, of using LOR, will get there before anyone else."

This tells you that, by golly, there was a space race in those days. As a sidebar, I did some work with National Geographic, working on a two-part docu-drama called Space Race. It highlighted two of the great giants in space activities. One, of course, is Wernher von Braun. It told his story of leaving Germany in 1945 and coming to Fort Bliss in El Paso, creating and working for the Redstone Arsenal for the Army, and later on developing and being the head of the Marshall Space Flight Center. It's a great story!

The other great giant of the space program was a Russian by the name of Sergei Korolev. He was in the gulag in Siberia because he had gotten himself into political problems. When the Russians discovered that there were rockets in Germany, they decided that he better come out of that gulag and participate in their young rocket program, which he did, and he was responsible for the booster activities throughout the Soviet Union until he died some years later.

I don't think, I'm not quite sure, that Wernher von Braun and Sergei Korolev ever met, but they -- I see a young lady who knows more than I do shaking her head "No" -- so, that was my belief as well. But, that story was called Space Race If you ever get a chance to look at it, it's a fascinating story about the lives and the contributions to our space activities, not only in the United States but by our adversaries, the Soviet Union.

Can you imagine managing those contractors who were involved in the Saturn V? I don't know how they did it. George, at headquarters, my hat is off to you. To Wernher von Braun and his people at the Marshall Space Flight Center, my hat is also off to you.

The first stage of the Saturn V was the S-IC. It was built by Boeing. The second stage was built by North American Aviation, Space Division. The third stage, the S-IVB, was built by Douglas. In addition to that, the engines, the F-1 and the J-2, were also constructed by North American Aviation, Rocketdyne Division.

There was an additional contractor that had to be managed. [A gust of wind blows across the podium.] There go my brains! It's windy up here! Are you guys enjoying the wind? [It was rather hot and humid, and the chairs were in a low spot in the Rocket Park, so any breeze was very welcome.] [laughter]

But the Instrument Unit, which was the brains of the Saturn V, was designed by Marshall and built, constructed, by IBM. Kind of goes together, doesn't it -- "brains" and "IBM."

There were two Saturn V unmanned launches, and then began the manned spaceflight program. I mentioned Walt's Apollo 7 flight in October of 1968. And the remaining flights of the Apollo program were all flown by the Saturn V. Apollo 8 through 17 were boosted by the Saturn V, and one additional Saturn V was used to launch Skylab, the laboratory itself. I think they stole it from me -- I was on [Apollo] 18 and I was supposed to fly. Did you do that, Owen [to Skylab astronaut Owen Garriott, who was in the audience].

Owen Garriott: "Not me!" [Laughter. Later that evening I asked Dr. Garriott if he'd ever been accused of stealing a Saturn V before; he admitted that he had not.]

Dick Gordon:

So, there were a total of 13 Saturn V flights.

The thing that astounds me about the whole program, the whole series of Saturn V, and my hat is off to those people involved and some of you are here this evening: There never was a mission failure in all of those flights. Yes, we had a component failure here and there. We had a couple of engine problems on the second flight of the Saturn V. But no mission ever failed, because of the great work that you folks have done here. [Applause.]

And an anecdote to my experience in the space program: I was a graduate of the University of Washington in 1951, and Uncle Sam said, "I need your services, young man." And I said, "OK, I'm going to learn how to fly." So, I join the Navy and became a naval cadet in Pensacola in the fall of 1951. During that time, as we were marching from class to class, one day they said, "You're all going to go to the auditorium to hear a lecture." And we said, "Well, OK" and we all marched into the auditorium, took our seats, a gentleman came out, and he started to give a lecture. He talked about spaceflight, manned spaceflight, orbiting vehicles, hotels that rotated that human beings would occupy, and we had yet to meet our first airplane. And we all kind of looked at each other, and we said, "This has got to be the craziest man we've ever met." His name was Wernher von Braun.

I told that story to Wernher many years later. He got a big charge out of it when we worked together on the Apollo program.

One other crazy person came into my life. In May of 1961 somebody said that we were going to go to the moon. Guess what? We did, with the help of you people here and that great, great Saturn series of rockets.

Thank you very much.

Actually, each of the last five Saturn I flights orbited Apollo boilerplates, and the final three missions additionally launched Pegasus micrometeroid satellites.

Additionally, the Saturn IB launched five manned missions: Apollo 7 and the three manned Skylab missions, as Gordon mentioned, as well as the American side of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project.

Larry Capps then introduced the evening's final speaker:

Astronaut Walter Cunningham is a native of Preston, Iowa and received undergraduate and graduate degrees in physics from the University of California at Los Angeles. Prior to joining NASA, he worked as a scientist for the Rand Corporation. On October 11, 1968, Walt served as the pilot of Apollo 7, the first manned flight test of the third-generation United States space craft.

Walt's last assignment for NASA was chief of the Skylab branch of the flight crew directorate, where he was responsible for five pieces of manned spaceflight hardware, two launch vehicles, and 56 on-board experiments.

Walter, welcome back to Huntsville!

| Time picture taken | Sat Jul 15 19:24:09 2006 |

| File name | dsc18698.jpg |

| Location picture taken |

Rocket Park US Space & Rocket Center Huntsville, AL |

| Prev |

heroicrelics.org USSRC Saturn/Apollo Reunions Site Index Third Annual Saturn/Apollo Reunion (2006) Gallery |

Next |